Click Here to Return to Home Page

The name Redruth is derived from words meaning 'red ford'. Until the 14th century Redruth was only a village. Then in 1334 the king granted the right to hold markets and fairs. (In the Middle Ages fairs were like markets but they were held only once a year and they attracted buyers and sellers from a wide area). However Redruth would seem tiny to us, It only had a few hundred inhabitants. Even by the standards of the time Redruth was a small town.

Redruth was, of course, in a tin mining district. Some of the town's people lived by farming or were craftsmen but at least some were miners.

Redruth grew slowly through the 16th and 17th centuries, despite outbreaks of plague. It struck Redruth in 1591 and in 1667-1668.

In the 1720s Daniel Defoe said that Redruth was 'worthy of no consideration'. However that was about to change. From the 1730's Redruth boomed. From that time steam engines were used to pump water out of mines. That allowed them to be dug much deeper and a mining boom began. Both tin and copper were mined. A writer said that: 'This town is of late years grown very considerable'. He added 'It owes its rise to the great confluence of people drawn together by the mines of tin and copper with which it is surrounded'.

For the ordinary miners life was very often one of hardship and poverty and it often ended early. Mining was, of course, a dangerous job. On the other hand life was hard for most people in the 19th century and many people did dangerous jobs. Many factory workers were poisoned by the materials they worked with. Life was cheap.

In the mid-18th century John Wesley, the founder of Methodism visited Redruth and Methodism took hold. The great preacher George Whitfield also visited Redruth.

Treleigh parish was constituted in 1846, being carved out of a northern section of the parish of Redruth and it covered 2200 acres, with a population of about 3000. Villages and hamlets within this rural parish, include Treleigh, North Country, a north section of Redruth, Radnor, Wheal Plenty, Parc Erissey, Sinns Barton, Forge, Gilbert’s Combe and North Downs.

During the nineteenth century the Parish gained considerable wealth through such mines as Wheal Peevor, United Downs, Wheal

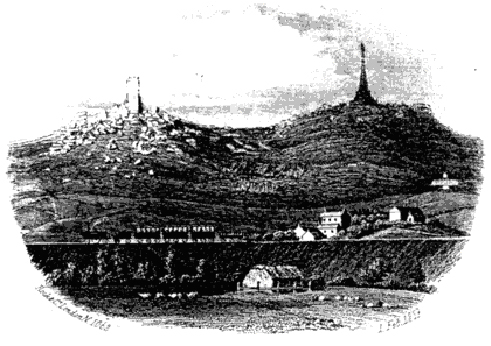

Redruth was formerly the capital of the largest and richest metal mining area in

By 1300 streamers were working along the brook that ran along the bottom of

Copper ore (discarded as waste by the earlier tinners) became sought after from the late 17th century. It could be used to make brass, a vital material for the technology of the Industrial Revolution. It was the deep mining of copper after the 1730s which raised Redruth's status to that of capital of the largest and richest metal mining area in

Tin mining had employed relatively few people, but copper mining was labour intensive. The population of Redruth and the nearby villages greatly increased. Despite this rapid expansion, and the vast fortunes produced by mines often within only one or two years, conditions in the mines were dreadful. Accidents were frequent, and there were many deaths. Life was cheap. The average life-span of the miners was under forty. Women worked on the surface handling the ore as bal maidens, and children started work as young as eight. Most mining families were desperately poor.

The long decline, brought about by international competition, began in the l860s. By l880 two-thirds of Cornish miners had emigrated to the mines of the

Click

Here to Return to Home Page